Wayne County agencies have plans for derailment, other hazmat responses

Despite being as prepared as possible for an accident involving hazardous materials, local fire and response managers agree that no one agency can be completely ready for something like the derailment that occurred Feb. 3 in a small Ohio town.

In East Palestine, Ohio, 38 freight cars derailed, including 11 carrying hazardous materials. Five carried vinyl chloride, a chemical used in making plastics. Exposure to it can cause a rare form of liver cancer and breathing problems. An area around the accident larger than Hagerstown was evacuated.

Firefighters are among first responders when rail cars leave the tracks. Railroads are often called upon to transport hazardous materials. Because of that, all firefighters with the Richmond Fire Department and volunteer firefighters outside of the city are trained in how to respond to hazardous material — called hazmat — incidents.

“I don’t think there’s any department that’s going to be able to handle (by itself) the initial response” to an accident like that, said Rick Cole, Hagerstown Fire Department chief.

Richmond Fire Chief Tim Brown agreed, saying that every incident will be different. “Any fire department is going to have to have help” unless it’s a major metro department, he said.

Far more common than derailments are truck accidents on highways and local roads involving hazardous materials such as farm chemicals and fuel.

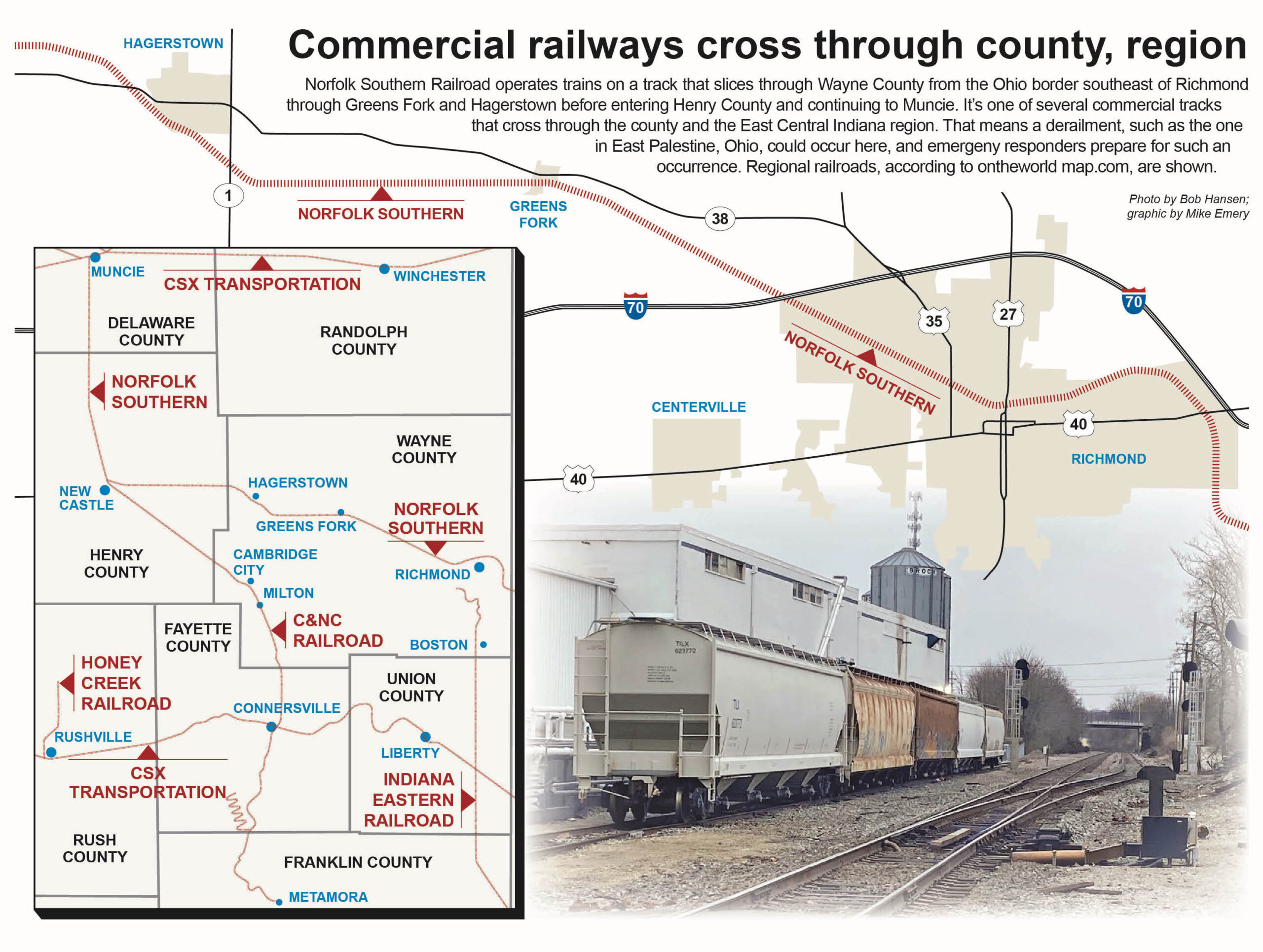

Still, the Feb. 3 incident weighs on the mind of Rick Stewart, chief of the Clay Township — Greens Fork Fire Department. He is glad that he and other responders participated more than a year ago in a daylong meeting with Norfolk Southern railway — the same company involved at East Palestine — and the Wayne County Emergency Management Agency.

“We have a plan in place” if there is a large derailment, Stewart said. “We would activate our mass casualty system.”

The Feb. 3 derailment resulted in a fire that burned for two days. While the five train cars carrying vinyl chloride remained intact after the derailment, officials decided to empty and burn the chemical because of fears of an explosion. The chemical releases hydrogen chloride and phosgene gas into the air, but federal officials say it was not concentrated enough to harm most people and animals. They’ve also said water pollution was negligible.

Norfolk Southern has a busy freight line that brings freight trains through Richmond and central Wayne County, including Greens Fork and Hagerstown. The train that derailed had crossed northern Indiana on another NS line, and local responders know the same kinds of hazardous materials could be coming through daily.

In any of these situations, local responders follow the National Incident Management System. It’s the same in East Palestine, a town of nearly 4,800 residents on northeast Ohio’s border with Pennsylvania. Since the East Palestine Fire Department’s initial response on Feb. 3, more than 70 local, state, federal and private agencies have been part of the response and ensuing cleanup.

A key part of NIMS is the Unified Command system, which provides a framework for coordination of firefighters, police, local emergency management agencies, ambulance providers, health departments and hospitals. All are trained in that system.

Here, a Local Emergency Planning Committee and the Emergency Management Agency staff develops and updates detailed records of where materials are stored and the kinds of things first responders can expect in responding to sites all over the county. Together, the responding agencies practice with local drills and mock disaster simulations, said Jon Duke, Wayne County Emergency Management Agency assistant director. After a review of the exercise, the LEPC updates its procedures to reflect what could have been done better.

The railroad company also has response units that work with local agencies, Duke said.

The fire department’s job is to try to contain any spill and fire, Brown said. Other agencies have other tasks, and cleanup is the owner’s responsibility — a railroad company, in the case of derailments.

In any major accident or emergency, two things happen immediately. First responders assess the situation, determining the nature of the problem, while the agencies set up command centers, one near the site and the other at a predesignated central location, such as the county communications center or a fire station.

Stewart said the first responders called to the scene are looking for three things: “Which way is the wind blowing, what color is the smoke, and what’s leaking.”

Smoke color can show the kind of material that’s on fire; wind direction signals where not to put responders and command centers and what areas might need to be evacuated.

In determining what’s leaking, responders rely on placarding. The federal Department of Transportation requires every train car or motor vehicle carrying any hazardous material to have a placard visible on its exterior. The placard’s color and a code printed on it tell responders what kind of substance is inside.

In addition, Duke said, in the case of railroads, he has access to a phone app from the railroad that will tell him what each and every car on a specific train is carrying. The EMA shares that information with responders. Many fire officials also have the app available.

Stewart said he and two assistants carry small books with pictures of the placards with their gear.

Every placard corresponds to a page in the DOT’s Emergency Response Guidebook, Duke said. It details health concerns, the protective clothing that responders should wear when a substance is present, what to do in case of a spill or leak, and when to order evacuation, Duke says. The ERG is available online to agency leaders.

“Once we identify the product and what state it’s in, we can formulate a plan and decide what are the next steps,” Brown said. “We have to take a methodical approach; we can’t just go in and start throwing water on it. On some products, water just makes it worse.”

At the on-site command center, equipment and personnel can be stationed and dispatched. At the distant incident command center, designated leaders from responding agencies direct the overall response.

For Greens Fork, Stewart’s plan would include contacting the Emergency Management Agency to bring their mobile command center. It’s a recreational vehicle outfitted with 911 emergency communications equipment that would be placed upwind from the accident. He would rely on the EMA to call out other fire departments: something on the scale of East Palestine would require response from Richmond and all county departments, as well as hazmat units from Indianapolis, Richmond and other locations.

The command center system developed after 9/11, when personnel from response agencies had a hard time communicating with each other.

“It’s unified,” said Joe Buckler, a Richmond assistant fire chief. “A leader from the fire department is in it, a leader from the police department, someone from the railroad, and so on, because they know what resources they have and what they can do.”

After decisions are made, each agency has jobs to do and it’s clear who is responsible, Joe Buckler said. “We work on a chain of command.”

His brother, Andy Buckler, is Richmond’s deputy fire chief in charge of training. He said that all 82 Richmond firefighters are trained in hazardous material awareness and operations. Additionally, 21 firefighters are trained at the higher hazardous material technician rating, which requires 100 hours of instruction from the State Fire Marshal’s Office.

All 25 volunteer firefighters at Hagerstown have the same basic hazardous materials training, Cole said, but none are trained at the technician level. For that, they would rely on larger departments. Greens Fork has 22 firefighters and all but three new recruits have the basic hazmat training.

Brown said the city and local volunteer departments have good working relationships and help each other as needed. Cole agreed and said Hagerstown also can call on New Castle and Anderson, as well as an emergency management regional headquarters in Delaware County. Resources can also be summoned from the Indiana Department of Homeland Security and even the Indianapolis Metropolitan Fire Department.

All the fire departments also prepare by keeping protective suits and gear on hand. Depending on the situation, different gear can be required. There are at least three kinds of protective suits. Richmond would send eight to any serious incident, Brown and the Bucklers said. At the scene, two suited firefighters could be sent into the situation while two more would be suited up to relieve or rescue the first two, if needed. Another set of four suits would be on hand for the next shift of responders.

A fully encapsulated class A suit costs about $2,000, Brown said, and must be replaced after its use or, even if not used, about every 10 years for safety.

Hazmat scenes also require decontamination centers, Brown said. These are portable showers where firefighters can remove the hazmat suits and scrub material off themselves and their equipment. In large-scale serious situations, the regional emergency management agency might set up its temporary hospital and call in appropriate medical personnel.

The situation at East Palestine, while tragic for that community, has gained notoriety as politicians have become involved, with many calling for increased attention to railroad safety. While local officials agree that safety and preparation is important, they also say that rail is one of the safest forms of transportation.

Even minor derailments are extremely uncommon. Brown remembers one in Ohio not long after he joined RFD 35 years ago. Cole remembers responding to one minor derailment — with no hazardous materials — in his more than 30 years on HFD.

A version of this article appeared in the April 5 2023 print edition of the Western Wayne News.